Spring is finally here, to the delight of those who enjoy walks and picnics in the great outdoors. But like every year, it also marks the return of a few unwanted visitors we could do without, starting with those pesky mosquitoes. And American researchers have just identified a mechanism that could explain their propensity to ruin our barbecues.

A team from Princeton University has focused in particular on a species called Aedes aegypti. It's a particularly problematic little beast because it can carry a whole cocktail of pathogens like malaria, the arbovirus Zika, dengue fever or yellow fever. And it turns out that in just a few decades, this particular mosquito species has evolved to target a single species almost exclusively: us!

From a biologists' point of view, this is a very interesting transition. This suggests that to survive depending on a single species, they had to develop incredibly precise targeting strategies that researchers have been trying to understand. Their ultimate goal: to determine precisely the mechanisms that allow mosquitoes to detect humans.

“We more or less delved into the mosquitoes’ brains to ask them: what do you smell? What activates your neurons, what lights up differently in your brain when you smell a human?” summarizes Carolyn McBride, professor of evolutionary biology, ecology and neuroscience at Princeton University. “

A treasure hunt based on smells

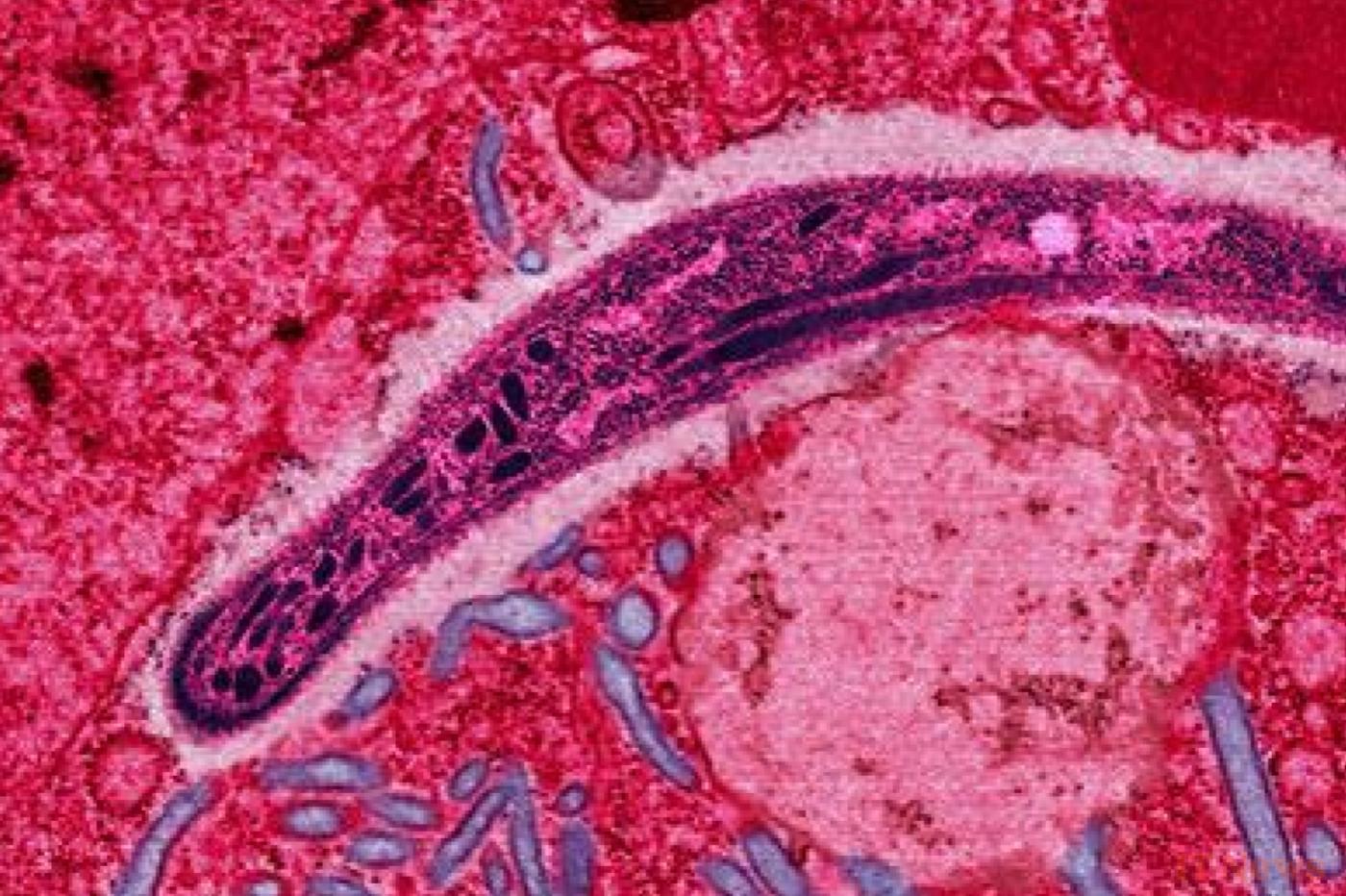

To achieve this, the researchers developed a very visual approach. They produced a genetically modified strain of mosquito whose nerve structures light up selectively when activated. They then exposed these mosquitoes to animal odors, including human odors, to try to shed more light on this mechanism using a specially designed imaging system.

The problem is that there are as many human odors as there are individuals. And for good reason: this odor comes from a very complex cocktail of dozens of organic compounds. The researchers therefore suspected that the mosquitoes were reacting to a very specific combination. But how could they find it?

Without any initial leads, they had no choice but to proceed empirically. They began by collecting the odors of rats, pigs of guinea pigs, quail, sheep, and dogs. But for humans, it was more complicated; collecting “pure” human odor is less obvious than it seems. Indeed, the majority of us regularly use scented hygiene products. Even clothing can considerably alter this odor.

A few volunteers therefore had to give of themselves. “We asked them not to shower for several days, to undress, and then to lie in a large Teflon bag,” says Jessica Zung, a member of the research team. They then had to develop a system that allowed them to extract and isolate these odors.

A surprisingly simple process

It still remained to determine precisely which compounds are likely to make mosquitoes react. The researchers therefore spent many months subjecting the mosquitoes to many combinations of the different compounds identified during the collection. They then cross-referenced the results to determine the most effective markers.

The researchers expected to discover a highly sophisticated tracking system. But the process they identified surprised them with its simplicity, since it is apparently based on only two specific organic compounds: undecanal and decanal, an aldehyde also found in buckwheat, coriander essential oil... and the famous Chanel N°5! A word to the wise...

The other point that surprised the researchers was the reaction these compounds provoke in the nervous system. The mosquito "brain" is a structure composed of about 60 substructures called glomeruli. The researchers expected that the majority of these glomeruli would be involved in hunting humans, since this is a vital activity for these mosquitoes; there are actually only... two.

“When I first saw this brain activity, I couldn’t believe it,” explains Zhilei Zhao, a doctoral student who played a central role in this study. “There were only two glomeruli involved, which contradicts all our expectations. It’s incredible that this system is so simple,” she marvels.

The door open to very concrete solutions

This discovery will potentially have considerable consequences, some of which are very concrete. Because this work was conducted on mosquitoes known to be vectors of very problematic diseases. Now that researchers have found the chemical compounds that attract them the most, this opens the door to a whole host of countermeasures to combat this public health scourge. For example, it would be enough to use them to lure them into a deadly trap.

We can also imagine repellents that would specifically block this signal, thus preventing mosquitoes from detecting humans by smell. This is an even more interesting solution. Because even though they are annoying, mosquitoes remain key players in many ecosystems.

For example, many birds and spiders depend directly on mosquitoes, as they represent a significant part of their diet. Ideally, it is better to try to keep them away rather than eradicate them, as this could signal the start of a catastrophic chain reaction for certain ecological niches.

Ultimately, it will also be very interesting to extend this work to other species. This will initially allow us to see if the mechanism is reserved for these specialized human hunters, or if it is, on the contrary, universal among all mosquitoes. If so, it would then be possible to develop a simple, harmless, and ecosystem-friendly solution to avoid serving as a walking buffet. Good news for fishing and picnicking enthusiasts... but especially for all the populations in tropical areas whose lives can change completely because of a simple mosquito bite.

The text of the study is available here.

0 Comments