In June 2024, Steven Barrett came full circle. After years as head of MIT's Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, he returned to where it all began for him: the University of Cambridge. But this wasn't just a homecoming. It was a passing of the baton between two of the world's greatest research centers, a sign that the challenge he was tackling extended beyond academic boundaries.

His primary mission was to advance knowledge about the environmental impact of aviation. This work also led to a second phase: encouraging collaboration between science, industry, and policy—the cohesion essential for any major challenge. By 2050, air travel will carry 10 billion passengers per year. And its impact is already significant, representing 2.5% of global CO2 emissions.

Cambridge understands this well. To welcome its former student, the university reserved a special place for him: the Regius Chair of Engineering, created by Queen Elizabeth II in 2011. In this capacity, the researcher was closer to Europe, and in particular to Airbus. The aircraft manufacturer made him a research partner and gave him an unprecedented task: to go to its nerve center in Toulouse and acknowledge at a conference what Airbus has never acknowledged: the impact of "contrails" on the climate.

"The equivalent of 60 years of CO2 erased"

That day, the researcher didn't beat around the bush. With a panel of guests including Mark Bentall (Head of Airbus Research and Technology), Tim Johnson (Director of the Aviation Environment Federation), and Ilona Sitova (aviation sustainability expert at Eurocontrol), Steven Barrett unveiled the collateral impact of condensation trails formed at the rear of aircraft and commonly known as "contrails."

The university professor compared their impact to that of CO2 emissions, in a completely new way for the aircraft manufacturer. "It is now estimated that CO2 in the atmosphere and contrails have a similar role in global warming. It's uncertain whether the impact of contrails is on the same level as that of CO2—maybe half, maybe double—but the two are in the same ballpark."

From this comparison of CO2 and contrails on global warming, Steven Barrett came to mention an important figure."As for warming from CO2, it's the result of 60 years of accumulated emissions since the jet age. Because once you release CO2 into the atmosphere, it stays there and accumulates. Contrails persist for up to 6 hours. That means the last 60 years of CO2 emissions from aviation have a similar effect to contrails over a 6-hour period."

Faced with this, Steven Barrett was optimistic. "Contrails are a very powerful constraining agent. But they offer a significant opportunity: if we could eliminate their formation in the air, it would be equivalent to canceling out the impact of aviation on the climate over decades. This is a huge opportunity to massively reduce the climate impact of aviation." A major speech, during a "Summit" where Airbus was quick to invite the world's press to "sincerely discuss the challenges facing the industry".

Pacific Project

For a long time, condensation trails cast a shadow. But rather than veiling the sky and trapping light rays, these contrails fueled conspiracy theories, around a possible diffusion of chemical products. The famous "chemtrails" (contraction of "chemical" and "trails").

"In 5 to 10% of cases, the exhaust gases released by aircraft crystallize, disperse, and end up forming wide bands,"preferred to point out Thomas Viguier, Energy and Climate Specialist at Airbus. The problem is that, like high-altitude clouds, these contrails reflect the sun's rays reflected by the Earth, and contribute to global warming. "In some cases, contrails have the opposite effect, and, like some clouds, contribute to lowering temperatures. But they are a minority," the manager qualified.

During its Airbus Summit 2025, the aircraft manufacturer acknowledged that it was indeed a question of chemistry. But of the chemistry of the fuels, of the kerosene used. Although the formation of condensation trails occurs due to the presence of air laden with moisture, it also requires the diffusion of fine soot particles, a waste product dispersed by the reactors once combustion is complete. To work on fuels less conducive to the formation of contrails, Airbus has announced the launch of the "Pacific" project. Announced by Mark Bentall of the R&T department, the program focuses on full-scale tests of condensation formation in aircraft exhaust gases, recreating the favorable conditions at high altitude, directly on the ground, in "cloud chambers." Until now, Airbus's research has focused on a program called Volcan, which required flying an A320 (which came at a cost) in airspace conducive to contrail formation.

"With this project, we're going to take one of our A350s on the ground, we're going to put a probe on the back of the Rolls-Royce engine, and we'll be able to operate it in what I would call a cloud chamber. We'll be able to test it and reproduce contrails in a controlled environment, and see how the different characteristics of kerosene can change the formation of contrails," explained Mark Bentall.

The importance of fuel and engines

While the tests are being carried out with conventional kerosene, they will also, and above all, focus on analyzing the fuels of tomorrow. With the Volcan program, Airbus already discovered that new sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) could reduce the formation of small ice crystals by around 25%. A question of soot residue. Because if condensation trails are the result of humidity and small pieces of ice, they also persist, and especially, with the ice crystals formed around these micro-particles.

SAFs should naturally combat the formation of contrails, which will not be the case with the hydrogen-powered aircraft. By not releasing CO2 but only water vapor, the risk of aircraft contrails multiplying increases. Fortunately, scientists believe that these would disperse more quickly, because the particles would be heavier than kerosene soot. But the fact remains that a hydrogen-powered aircraft would release a lot of water vapor, and tests would be needed to get a better picture. A study at Airbus should provide results this year.

"When it comes to hydrogen, we have an experiment with a Blue Condor. Many people ask me when this work will take place. The plane has already flown (it was due to make its first flight in November 2023 editor's note), and it is now up to the academic world to analyze its measurements. We hope to publish results in the fourth quarter of this year," declared the Airbus manager. Two years ago, the aircraft manufacturer already acknowledged that hydrogen could create "up to 2.5 times more condensation trails" compared to current kerosene.

On the Airbus A350 requisitioned for the Pacific project, the engine will also be inspected. The reactor will also play a role in reducing contrails in the sky, and Mark Bentall stated that Airbus was working with its partners (by which we mean CFM International and Pratt & Whitney, in addition to Rolls-Royce). "We are conducting lean burn and rich burn tests, testing different temperatures, and analyzing the impact of lubricants in the engines." These reactors will drastically change their design and operation by 2035.

Decrease in contrails = increase in kerosene

Obviously, the engine and fuel will not solve the entire problem. Another, much larger dimension must be taken into account for a sky without contrails. This other project will take place in air traffic control centers, and on maps, thanks to the detection and prediction of areas where conditions are favorable to the condensation of exhaust gases.

For Mark Bentall, this part will certainly be the most critical, because it will involve a counter-intuitive decision: modifying the trajectory of aircraft at the risk of increasing their fuel consumption. To achieve this, it will be necessary to "absolutely understand what we intend to eliminate, because when we start operating, we will also have to consume more kerosene," acknowledged Mark Bentall.

Reducing contrail formation will require changes route, even if the Airbus manager favored the option of flying "above or below" the areas to be avoided. "We certainly won't go around them," he added. Flying below them will, however, increase engine consumption, while altitude plays a role in kerosene use: the higher the plane, the less air resistance it encounters.

Steven Berrett, however, called for pragmatic action. "I think we should recognize that reducing contrails offers clear benefits, with more trivial drawbacks. Eliminating contrails could reduce the impact of global warming by 2%, an effect equivalent to the combined impact of France and England on the climate." At the same time, limiting contrails would lead to a 1% increase in fuel consumption in the aviation sector, which represents only 2% of global CO2 emissions."

Satellite surveillance and prediction models

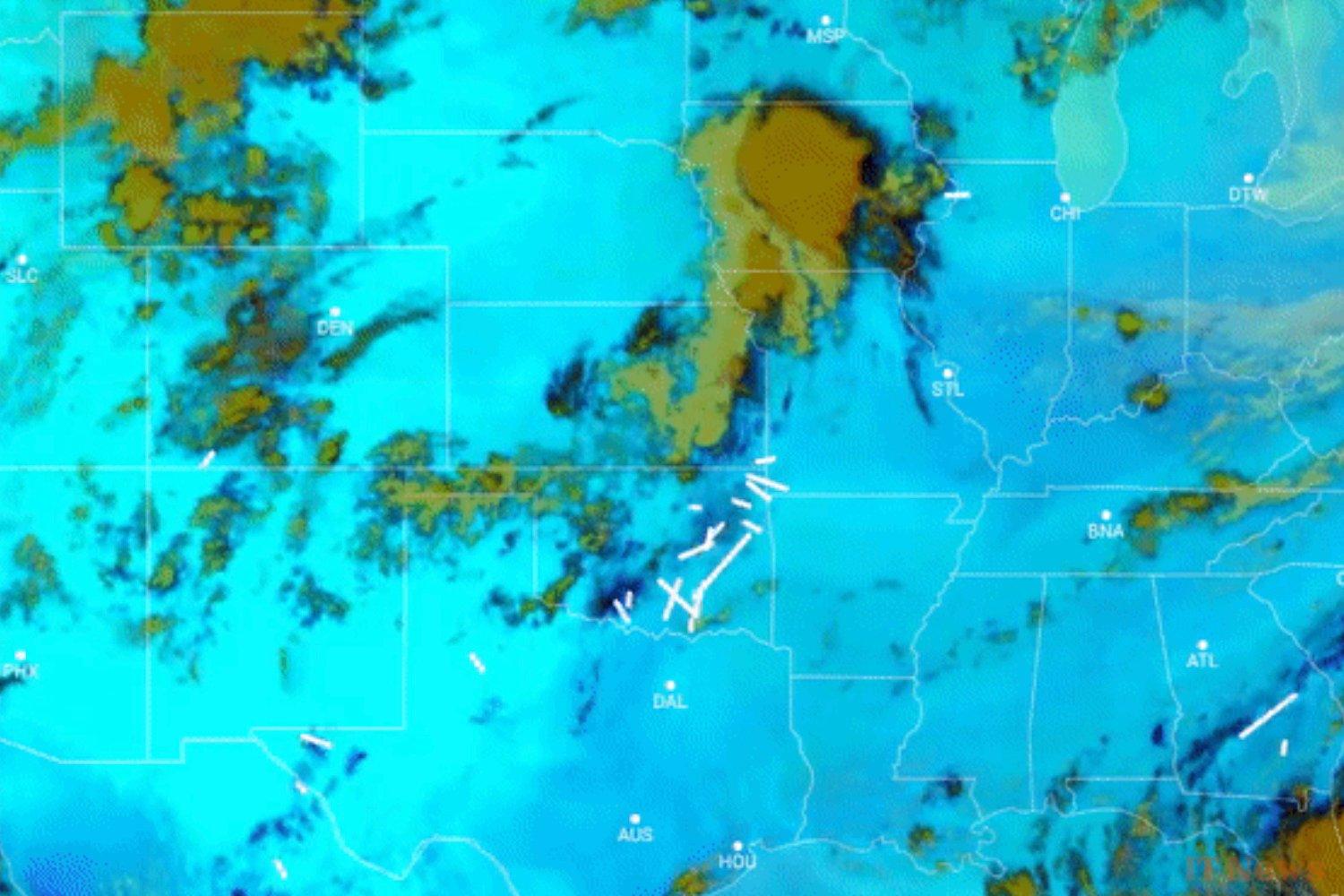

We will still need to know where these areas are, before being ready to include them in the list of reasons for changing an aircraft's trajectory. For researcher Steven Barrett, geostationary orbit and low Earth orbit already offer us the means to keep an eye on risk areas.

He mentioned the arrival of a new geostationary observation satellite, over Europe and Africa, "which provides real-time imagery useful for spotting contrail formations." Similar satellites also exist for the Americans, and more recently for East Asia, thanks to the Japanese space agency. A constellation of low-orbit satellites called FireSat, launched by Google in March 2025, could also play a role, even if it was initially deployed to prevent fires.

"Simply put, I think that, in the same way as the observations we make for turbulence, we will be able to detect in real time the regions where contrails are forming to tell pilots to fly 2,000 feet lower. Over time, forecasts will improve, and we will be able to eliminate contrails by 50%, then 80%, then 90%, etc.," Steven Barrett maintained.

One voice on the panel did, however, speak out against Steven Barrett's comments, and against the observational approach. It was Ilona Sitova, speaking on behalf of air traffic control centers. The aviation sustainability expert for Eurocontrol's MUAC pointed out the simplistic reasoning that it would be enough to change the route of an aircraft. "The deviation of one aircraft would cause the deviation of many aircraft. And that would pose safety problems, so we would have to regulate traffic and keep planes on the ground.".

Rather than observation, Ilona Sitova advocated the idea of "favoring predictions", and emphasizing verification. "We need to know if we are doing the right things. Otherwise, we will burn more kerosene without any benefit," warned Ilona Sitova.

Conflict between scientists and decision-makers

In the grand scheme of things, Airbus does not see changes coming without being motivated by political initiatives. For the aircraft manufacturer, as for researcher Steven Barrett, nothing will take shape without the prior impetus of a regulatory change.

"The free market and manufacturers will not take the first step. In parallel with the fight against CO2 emissions, we need regulations. Those who will provide the reasons to eliminate contrails are the regulators and politicians. If they provide the impetus, then we will find a way to meet their expectations. We are not talking here about solving the problem of nuclear fusion; it is simply a question of software to redirect aircraft and observation tools to identify where condensation trails form." It's entirely feasible."

Guy Johnson, the roundtable's mediator, turned to Tim Johnson, director of the Aviation Environment Federation (AEF), for his opinion. More accustomed to dialogue with policymakers and regulators, he illustrated the difficulty of moving forward at the speed desired by Steven Barrett. "Condensation trails will also need to be monitored. But we need advances from the scientific world first, to obtain the necessary data on a large scale. I think the next two or three years will be critical in providing us with these answers," he said.

Momentum

Behind the presentation of the challenges and difficulties of eliminating condensation trails, a big question: why are we only addressing this now? Why not have addressed this five, ten, or twenty years ago? While Steven Barrett advocated the constraint agent as an opportunity to have an "immediate" positive impact on the climate, it is difficult to understand how the machine did not start up sooner.

Ilona Sitova confided that at this stage, "it's a research project, purely". Tim Johnson acknowledged that the research has come up many times. "We've been talking about it for years, actually. We've come very close to achieving it in the past—and when I say "the past," I mean about ten years ago. This time it's different. The momentum isn't just coming from Europe; it seems to be global. Interest has spread to ICAO, we've attracted the attention of the general public, and we're conducting operational tests." I don't think we'll be going backwards this time."

The director of the Aviation Environment Federation (AEF) added that, alongside the goal of net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050, "we should also foster the ambition of no longer generating additional warming linked to other non-CO2 effects by that time. I think that before, we couldn't see an immediate path forward, and we felt we didn't have the necessary data. The momentum was running out. This time, I really believe it's different."

The sickness of more efficient planes

Agreeing on the notion of momentum, Steven Barrett called for no more time to be wasted. "There are upper ranges and lower ranges. The scientific literature has constantly sought to reduce this range of uncertainty. But one thing is certain: this in no way undermines the consensus estimate of the warming effect. We have sufficiently strong evidence from this latest generation of research. Instead of racking our brains wanting more, which would require a new generation of research, we should take action."

Waiting another generation will complicate the task, because by then, the problem will worsen. And not only because of the growth of air transport. Although SAFs could reduce the risk of contrail formation by removing soot residue from the exhaust gases, improving aircraft efficiency also risks increasing the formation of condensation trails. Quite a paradox.

In response to a journalist, Steven Barrett explained this other counterintuitive trend regarding aircraft efficiency. "It is true that the more efficient an aircraft is, the more fuel is used for propulsion and the less it is wasted as heat in the aircraft's exhaust gases. So, old, inefficient planes left a lot of heat behind them, and all that heat made it harder for ice clouds to form. On the other hand, new engines leave colder air behind them and therefore create more contrails.

Boeing can count on Google and AI

The urgency will also be symbolic, and sovereignist. Europe is not alone in working on eliminating aircraft contrails. Across the Atlantic, research is beginning to bear fruit. On the issue of sustainable aviation fuels, Boeing, General Electric, and NASA have been conducting tests in Europe since 2015, in collaboration with the German Aerospace Center. In October 2024, their program ironically switched from an Airbus A320 to a Boeing 737 Max 10, equipped with more modern engines.

Even more striking, American work on contrails took on a new dimension when Google became interested in it in 2021 with "Project Contrails". The rise of artificial intelligence marked a turning point, making it possible to massively analyze satellite imagery to better predict contrail formation and optimize flight trajectories. In just six months of experimentation, on 70 flights conducted with American Airlines, Google announced a 54% reduction in contrails, with an increase in fuel consumption limited to 2%.

A program from which Airbus, visibly, remains aloof. During its Summit, the European aircraft manufacturer nevertheless organized a round table dedicated to artificial intelligence, which included Vincent Poncet, a Google executive. Despite many topics being brushed aside, AI to help contrails was the notable absentee. As if the subject no longer existed for anyone, and the idea of erasing aircraft trails was mainly about erasing traces—one's own traces.

0 Comments