It could be just any street in the suburbs of Lille – red bricks, shared scooters abandoned in the middle of the sidewalk, children's voices coming from a daycare. But yet, under the sunny sky of Roubaix on this Wednesday in May, Rue Kellermann is not just any street. Its rusty brick facades house one of OVHcloud's nine data centers in northern France: "Roubaix 8." Behind its walls are some of the "120,000 physically present servers" of the French cloud champion, representing nearly 20 to 25% of the group's worldwide activity.

With a fluorescent protective cap on your head and safety shoes on your feet, you must pass through a security gate that weighs you and takes your picture to enter the lair of Europe's leading cloud hosting provider. This is perhaps where the billion-euro French cloud computing champion hosts billions of data points from public and private entities. In recent months, their interest in a "European and sovereign cloud," a card brandished for years by OVH, has been multiplied after the American geopolitical turnaround. As we pass through a final control booth and enter the famous building, we think back to this promise, on paper, enticing: to be able to see and tell what is hidden behind our multiple digital consumptions: streaming, social networks, messaging, gaming and now AI tools like ChatGPT, Gemini and Le Chat, whose alpha and omega, the data, is perhaps stored here. For the first time for us—but not for 01net.com—we're going to see the structure, the equipment, the infrastructure that subordinates our thousand and one digital uses: the tangible behind the intangible.

A deafening hum

As soon as we enter, we hear the sound of ventilation. Above our heads, orange cables wind their way along the ceiling, several meters high. We still have to walk along a corridor that adjoins the electricity arrival and control rooms. These are isolated from the heart of the data center due to the risk of fire. For OVH's most recent infrastructure, all the energy has been placed outside the buildings. "Once you've been struck by lightning, you're inevitably more sensitive," explains Grégory Lebourg, director of environmental programs, referring to the Strasbourg fire that, in 2021, caused an OVH data center to go up in smoke. And while the causes of the fire have still not been publicly revealed, with the investigation still ongoing, the company has since implemented a "hyper-resilience plan." It has invested "€60 million in (its) data centers to ensure this never happens again," explains Solange Viegas Dos Reis, the group's legal director. While in 2021, "no company wanted to insure us anymore," the situation has now changed. Other cloud providers have also suffered incidents. And "the insurance companies are fighting to get us," she rejoices.

But that's it. We take the last few steps before reaching the heart of the data center, access to which is still restricted by a badge. A deafening hum overwhelms us, under an almost natural light. In front of us, no immense refrigerated cabinet rises to the ceiling. Instead, stands a first long aisle of "bays" nested in metal structures. The three-level complex towers over us by one or two meters.

In this sleek warehouse, where 86 employees work (out of the group's 2,800 worldwide), we walk along dozens of rows of racks, like long aisles in a vast library, each separated by a good meter and a half. Each rack is made up of several servers stacked on top of each other, like books—or rather, trays—stored horizontally on a shelf. We'll learn a little later that there are different combinations of racks, named after Mario characters like Luigi, Wario, and Toad. "In every square meter, there are between 25 and 60 servers," explains Antoine Renaut, regional data center manager.

In the realm of data and servers, there is also water

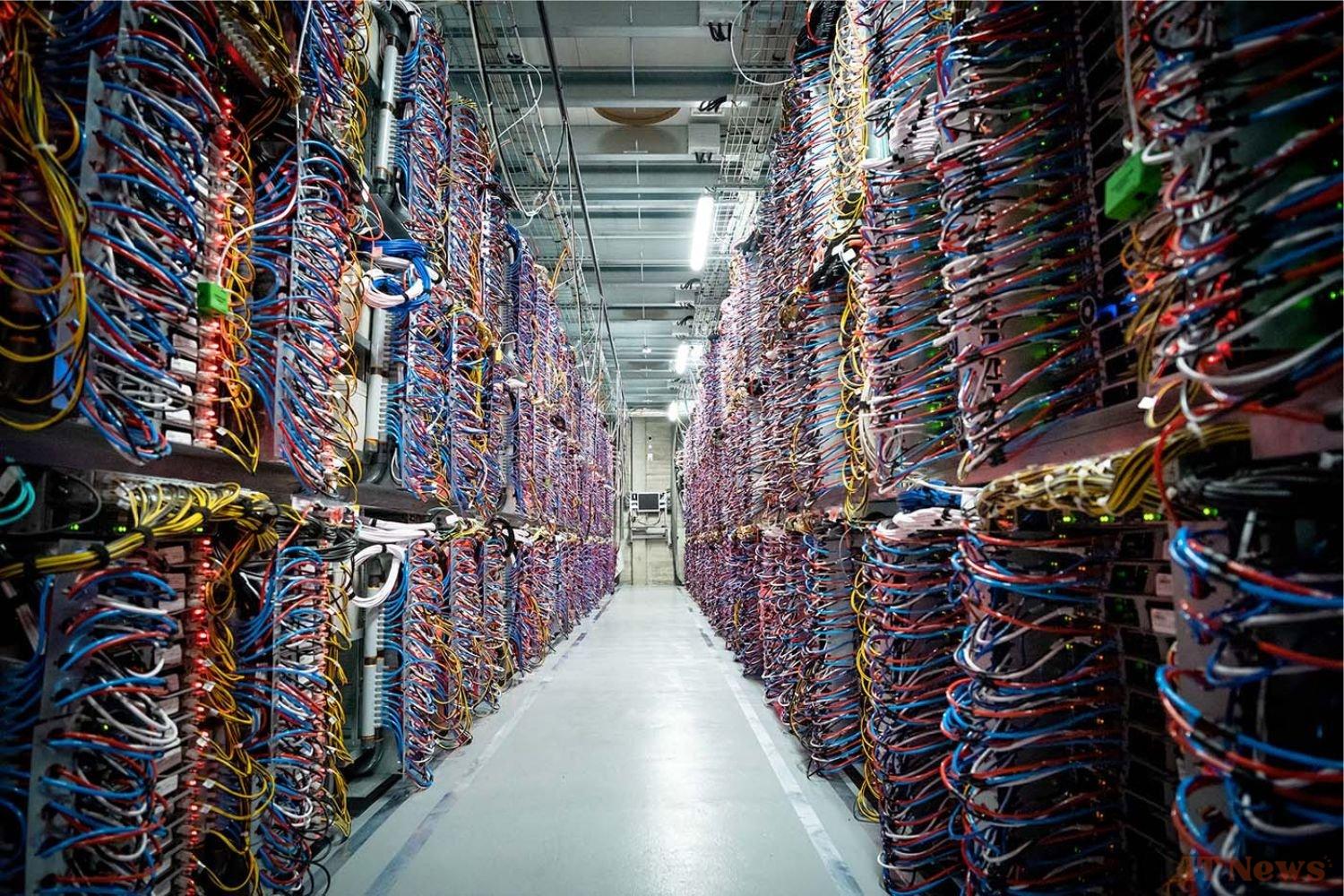

In the building, the density of servers gives this "library" a strange appearance: from its shelves emerge a thousand and one yellow, black, red, blue, white, and green cables. The impression of having opened the hood of an enormous machine that hums loudly, even though there is no hood, is persistent. Alongside the rather expected electrical and network wires, copper pipes complete the picture, with hot and cold water inlets and outlets. Because yes, in the realm of data and servers, we also find water and many elements that are more reminiscent of the world of plumbing.

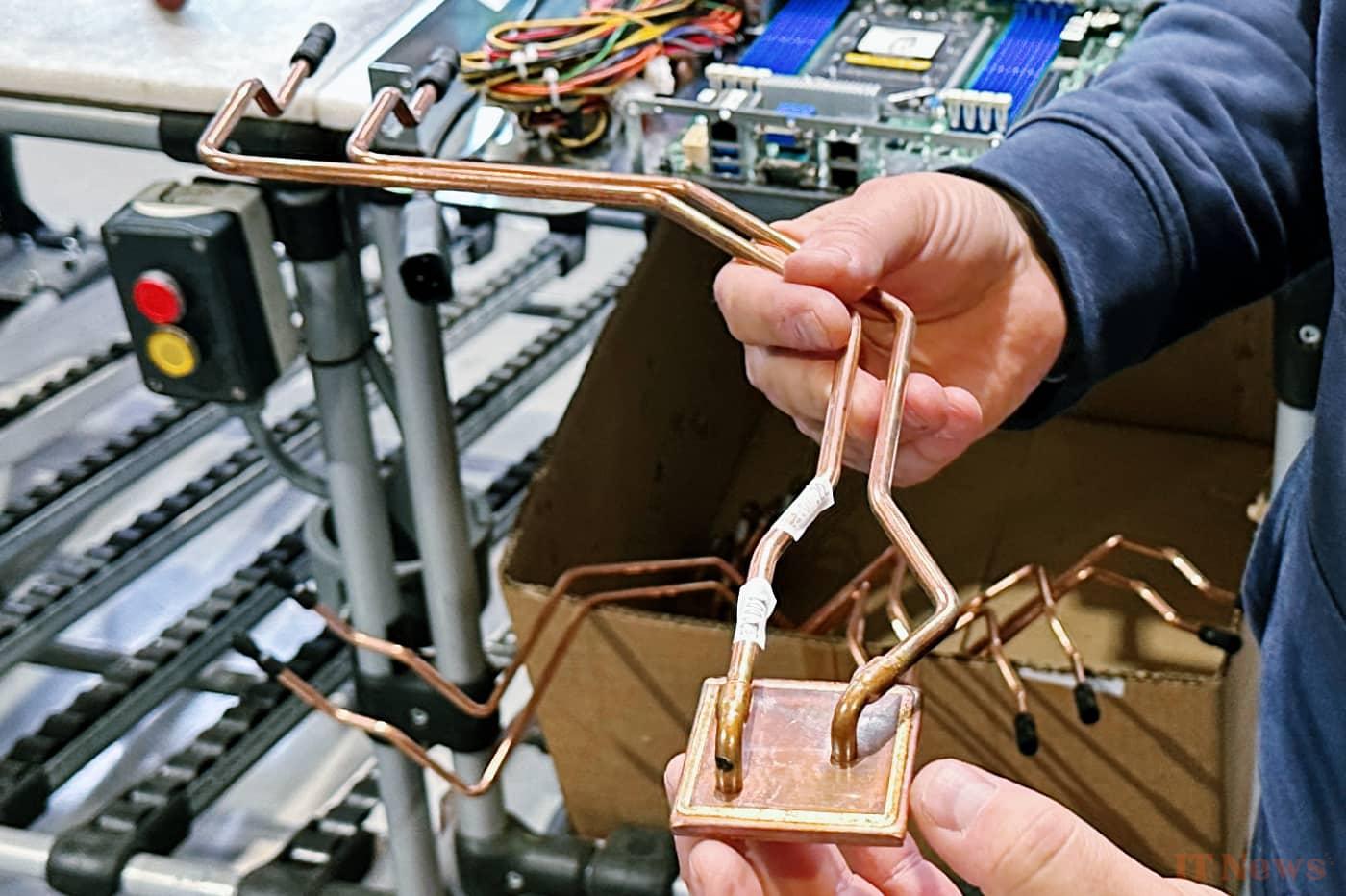

This is one of the particularities of the Ovhcloud data centers, created in 1999. "We are independent of the outside temperature," summarizes Grégory Lebourg, director of environmental programs. Unlike its competitors, here, there are no refrigerated cabinets, no air conditioning, even in summer. Inside, it is hotter that day than outside, but only by a few degrees. The reason is called "watercooling," a system for cooling servers using water invented by the Klaba family, including Octave, the founder of OVHcloud, in 2003. Installed on each server, the device removes nearly 70% of the heat emitted by the system. The technology is protected by "a hundred patents," Grégory Lebourg tells us.

In concrete terms, water is circulated through an exchanger placed above the processor to cool it. The water will capture the emitted heat – heat that will then be rejected outside, and sometimes reused for the company's needs. Thanks to this system, there's no need to thermally insulate the building. There's also no need to install an energy-intensive and costly air conditioning system: this will allow for substantial savings, address environmental issues, and keep up with American hyperscalers (AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud), acknowledges the director of environmental programs.

Each server also comes from OVH: they are designed and assembled in its Croix factory, located some six kilometers from the data center, which we were also able to visit: the site supplies data centers in Europe and Asia. For North America, a similar factory exists in Canada. Here too, we must imagine a warehouse in which lines of three operators will "clip" onto metal frames - manufactured a few meters from the factory - components from abroad, some of which are sometimes worth more than 15,000 euros each (motherboards, processors, connection cables, electrical wires, water and air inlets, etc.).

Then begins a veritable "Lego assembly" process that all new arrivals must go through, one of the employees tells us. He himself spent a week learning how to assemble a server when he joined the group. Design, logistics, assembly, testing, and recycling take place one after the other in the immense warehouse, which also includes a robotic section used for production peaks, emphasizes Frédéric Lockart, workshop manager and manager of the "Reverse" loop at OVHcloud (recycling). In concrete terms, "a server comes out every three minutes." Its lifespan can be up to nine years, with three-year cycles. "During their second and third lives, the servers still function well, but with less performance," adds the manager. Understand: not all customers need the latest generation of CPU/GPU to store their data.

Once the cycle is complete, the server components are dismantled: every week, between 500 and 600 servers are stripped. These are recycled at 60%: some parts are reused, others are given away or resold to brokers. Some of them, unusable, end up being crushed.

Roubaix 8 also has several SNC (SecNumCloud) or "Critical +" rooms, behind which the mystery remains intact - only a few authorized employees can enter, with fingerprints as proof. This highest cybersecurity label, which protects the data stored there from American and Chinese extraterritorial laws, is now required for certain sensitive government data.

"The servers in these rooms do not leave. They also have their own cooling system. We use specific network cables," we are told. To obtain this label, you must undergo an audit that lasts 12 to 18 months.

But for Solange Viegas Dos Reis, the group's legal director, the SNC label is far from the only asset that allows OVHcloud to be protected from potential pressure (commercial or geopolitical) that could come from certain countries – understand: the United States and China. "The fact that we manufacture our own servers and have our own telecom networks allows us to not be technologically dependent" (on companies or foreign countries, editor's note), acknowledges the legal manager. Add to that the fact that OVHcloud is still 80% owned by the family of Octave Klaba, its founder, she continues.

Has the group actually seen more customers knocking on its door since the American about-turn and the fear of seeing the three American companies that dominate the cloud market today (Amazon AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud) being exploited? "We talk to a lot of people. We now host the IGN and the CNRS." And if, in the past, "we perhaps had an image deficit compared to the big hyperscalers," today, "being at OVH is good, because we are sovereign," believes the legal director. "The good news is that sovereignty is now no longer a subject for IT departments, but for business leaders," she continues. The fact remains that once the decision to "switch to a European cloud provider is made, then comes the execution," a step that can take several months, or even several years, and from which OVHcloud hopes to be the lucky beneficiary.

And while it's already time to leave, and the doors are closing on OVH's northern premises, the servers continue to be assembled, tested, and dismantled. At the same time, a few kilometers away, passersby may be crossing rue Kellermann, far from suspecting that behind its facades, the Roubaix 8 bays and its thousands of colorful cables continue to hum tirelessly.

0 Comments