A tiny lunar fragment is intriguing scientists. This glass bead, brought back by China's Chang'e 5 mission, provides clues about the Moon's little-known interior. Its origins date back to a titanic collision in our satellite's distant past.

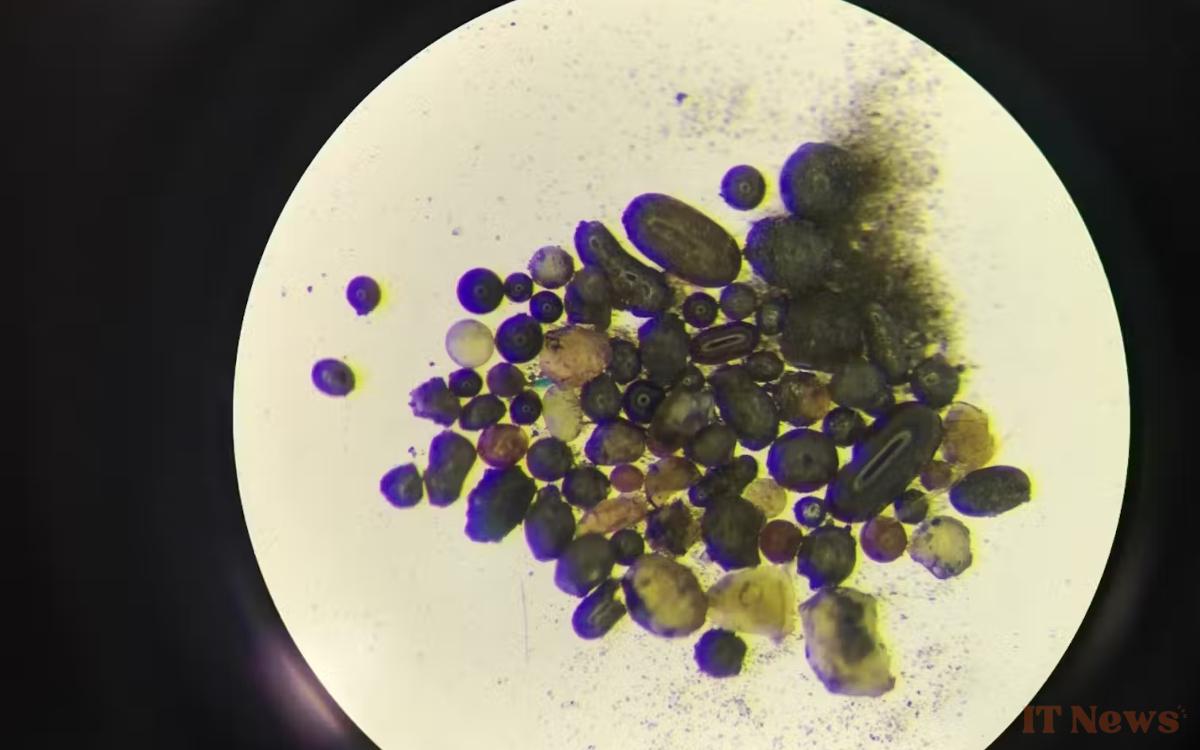

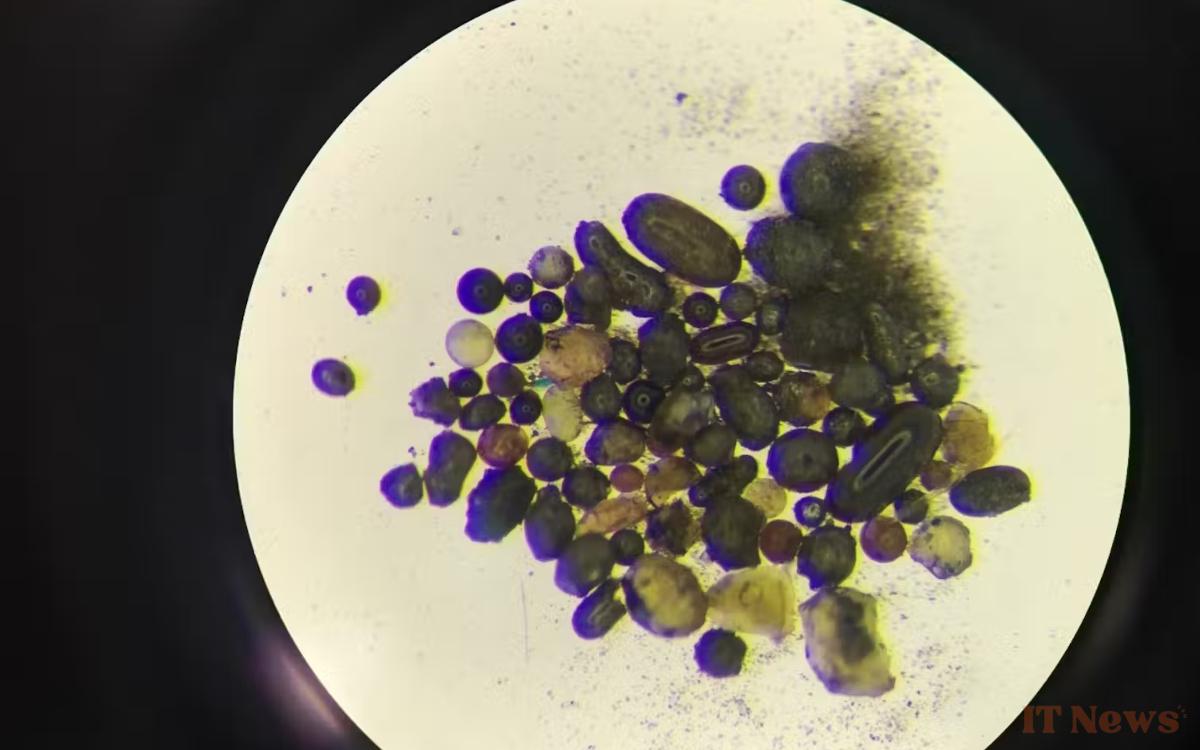

The Moon has long fascinated us with its craters, dark rocks, and violent history. Until recently, much of its interior remained inaccessible to study. The Apollo missions collected many samples, but all came from the surface. Since 2020, China's Chang'e 5 mission has brought back new, more recent fragments of lunar soil from a different region. Among the 1.7 kg of rocks collected, a tiny glass bead has caught the attention of researchers. Its chemical composition is very different from the usual volcanic rocks in the region. It contains a high concentration of magnesium oxide, a clue that suggests it may have come from the depths of the Moon, more precisely from the upper mantle. A hypothesis reinforced by new analyses conducted by a team of Chinese and Australian scientists.

A tiny ball formed by a double impact reveals the origin of the lunar mantle

According to the researchers, this ball was formed after an intense shock, which occurred around 68 million years ago. A small asteroid would have struck an area already weakened by a much older event: the giant impact that formed the Imbrium basin, nearly 4 billion years ago. This first impact would have already exposed deep fragments of the lunar subsoil. The second, more recent, would have melted these ancient debris, transforming them into small glass beads like the one studied today.

The interest of this discovery is major: if the bead does indeed contain material from the lunar mantle, it would allow us to learn more about the internal evolution of the Moon. Until now, no known sample came directly from it. Thanks to the gradual opening of Chang'e 5's collections to foreign laboratories, other more in-depth analyses could soon confirm this origin. Several institutes around the world, including one in France, are participating in this research, which could transform our understanding of the formation of our natural satellite.

0 Comments