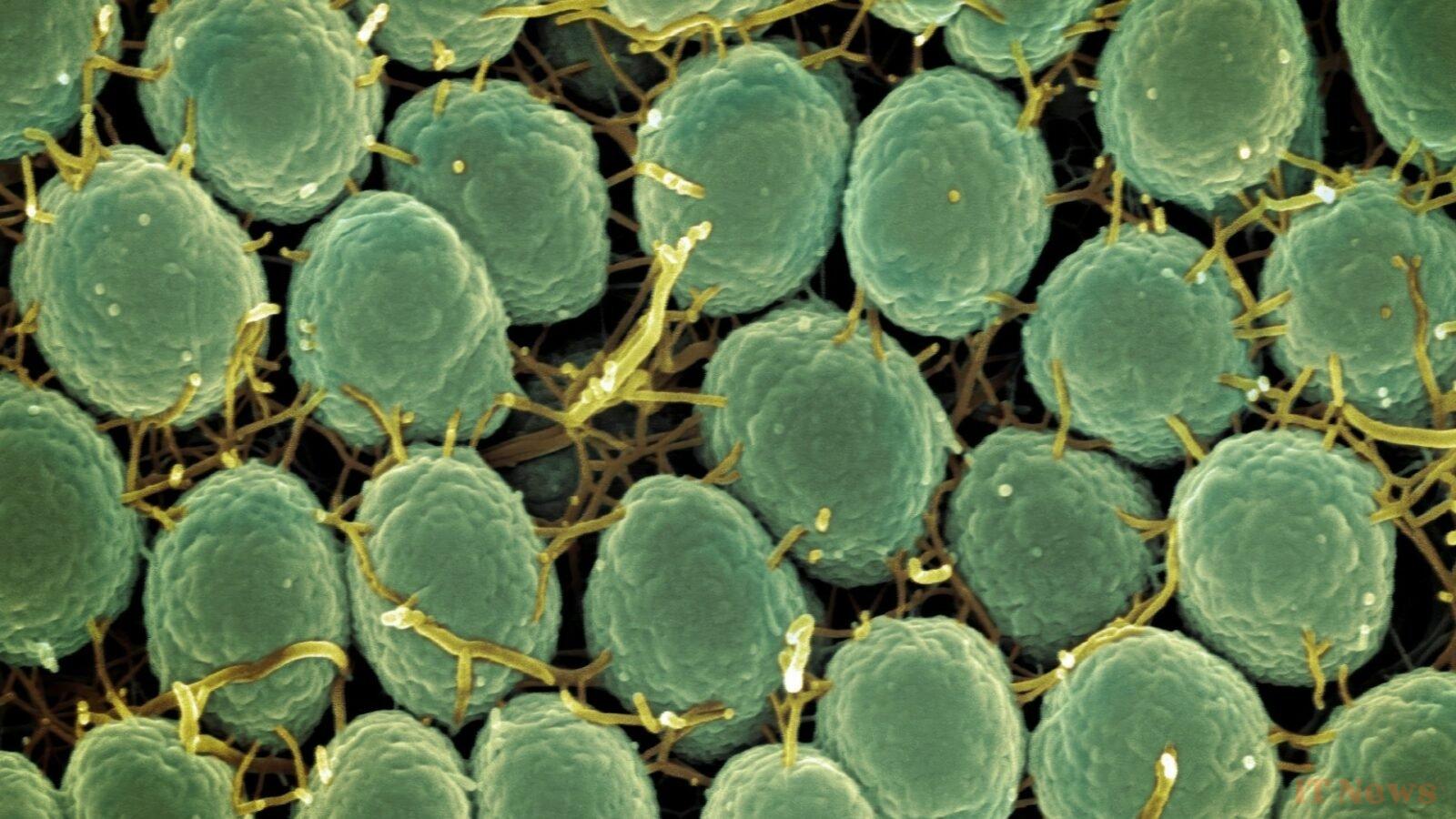

Two scientists from China are in the crosshairs of the American justice system. The duo allegedly attempted to smuggle a biological sample containing the DNA of Fusarium graminearum into the United States. This microscopic fungus causes Fusarium head blight (FHB), a disease that affects major crops such as wheat, barley, corn, and rice.

A destructive fungus imported without authorization

According to the prosecution, the researchers were fully aware of the restrictions related to this biological material and allegedly concealed the sample in a box of tissues upon their arrival in the United States in the summer of 2023. There is no evidence that the two researchers intended to spread the fungus outside of a laboratory setting. But they are nevertheless being prosecuted for conspiracy, false statements, visa fraud, and illegal introduction of regulated material.

Fusarium graminearum is strictly regulated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which requires a specific import permit. Neither researcher had filed an application with the relevant authorities.

The potential impact of Fusarium graminearum on American agriculture is far from trivial. This mold can destroy a promising harvest in a matter of weeks, especially if the weather is wet when the plants are flowering. The fungus then colonizes the ears, leading to grain loss and contamination by mycotoxins.

These toxins, such as deoxynivalenol (or DON, nicknamed "vomitoxin"), can cause digestive problems in humans (nausea, vomiting) and more serious effects in the event of chronic exposure: weakening of the immune system, neurological disorders, etc. In animals, they cause food refusal, diarrhea, lesions, or even hemorrhages.

The American food industry is very vigilant: brewers, for example, systematically refuse batches containing the slightest trace of vomitoxin. And even if cooking or milling processes can reduce these residues, the issue remains serious.

Another concern: the growing resistance of certain strains of Fusarium to fungicides. This complicates treatment strategies and encourages the search for new active substances or more resistant wheat varieties. As Gary Bergstrom, a professor at Cornell, points out, there is no miracle solution. Only integrated management—combining tolerant varieties, adapted agricultural practices, and targeted treatments—can limit the damage.

While Gary Bergstrom is reassuring about the potential for using the fungus for malicious purposes, he admits that unforeseen mutations, such as increased resistance to treatments, could pose a serious problem. Hence the importance of strictly regulating its importation.

0 Comments