The tension is palpable under the morning sun of the Aosta Valley. In Verrès, at the start of stage 20 of the 2025 Giro, the riders are warming up amidst the roar of a packed crowd. But behind the scenes, in the shadow of the peloton, another ballet is brewing: that of the Shimano neutral support cars, the famous "blue cars" that have become a staple in the world's biggest races. On this May 31st, we are on board one of them, to experience from the inside what few spectators see: the ultra-precise logistics of a technical service without jerseys, but essential to the race.

A military organization... but a mobile one

Shimano's neutral assistance service isn't just a visible brand on the side of the road or on the water bottles handed to riders. It's a European organization involving 50 drivers, 50 mechanics, 5 coordinators, and a manager, deployed over 450 race days per year in more than 240 races, in all disciplines of professional cycling. "We're the team with the most presence in the WorldTour, more than any other team," says our chaperone for the day, Massimo Subbrero, former sports director, now at the wheel of the car we're in.

On this 20th stage of the Giro, between Verrès and Sestriere, three neutral assistance vehicles are present, a motorcycle and a logistics van parked upstream to anticipate possible equipment transfers. The vehicles are distributed in the race caravan according to a precise plan defined by the race direction, in order to cover the main peloton, the breakaways and the stragglers. "We're the only team not racing, but we're here for everyone," our Italian driver explains.

A workshop traveling at 70 km/h

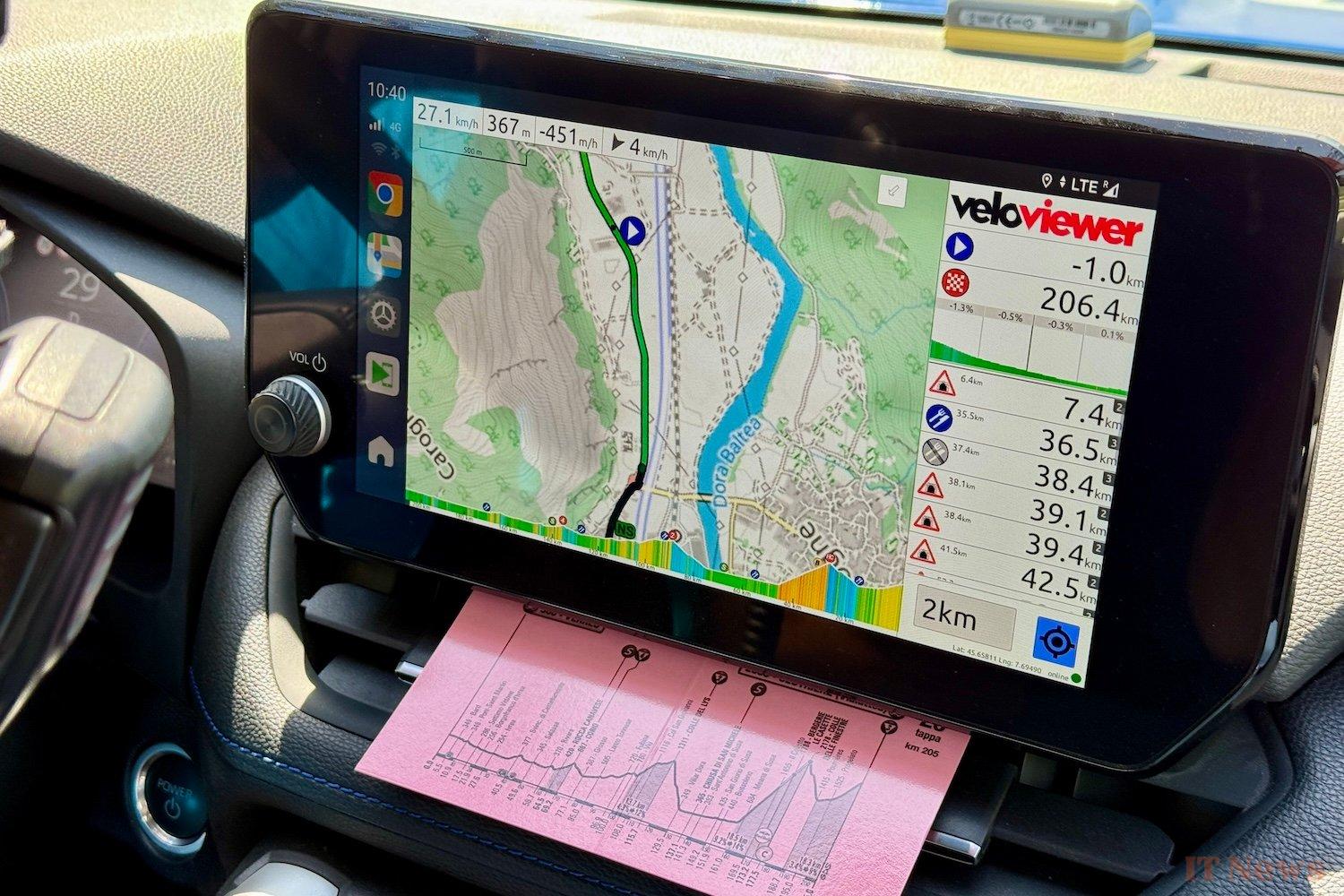

Our vehicle of the day, car number 1 placed just behind the breakaway, is a Toyota RAV4 hybrid, loaded like a real traveling bike shop. Inside, Diego, the mechanic on duty, gives us a quick tour: "We have 14 wheels in the back, 6 complete bikes on the roof, about ten derailleurs, several cassettes, pedals of all types (SPD-SL, Look, Time, Speedplay), specific tools, and even something to distribute water or gels if necessary." id="gallery-1-1275165"> ©

The different types of pedals available to cyclists. © JSZ — 01net.com

All the bikes on the roof are equipped with dropper posts, a design detail designed to accommodate any rider's size in case of an emergency."We even pre-set the seat heights of the top four in the general classification today," he explains. "If a leader gets a puncture and his team car is too far away, we can give him a bike ready in 20 seconds."

The emergency bikes are all equipped with a telescopic seatpost and a trigger to adjust it. © JSZ — 01net.com

The keystone of this system is anticipation. Every day, the mechanics study the makes and models used by the competing teams, identify the transmission variants (11 or 12 speeds, 140 or 160 mm disc brakes, etc.), and adjust the contents of the cars. "We have wheels with all possible wheel spacings and compatibilities," he continues. "You have to be able to change a wheel in less than 30 seconds, sometimes even while running alongside a rider who is still moving."

The components of a racing bike are not standardized. © JSZ — 01net.com

A race within the race

As the race gets underway, we discover a fascinating reality: being in a support car is like experiencing another race, parallel to that of the riders. The driver steers with surgical precision between the television bikes, the team directors' cars, the marshals' bikes, and... the riders themselves. The most impressive thing is the descents where you can reach 100 km/h in a straight line on a very narrow mountain road, just to avoid being left behind by the riders in front and not to hinder those coming up behind.

Communications are flowing via radio: a rider has a rear puncture, a crash has occurred, the leading group has a 30-second lead, all race information is delivered to the entire caravan in real time. Another internal Shimano radio allows communications between the brand's various vehicles. The driver adjusts his position, ready to pounce when the peloton splits: "You always have to be in the right tempo, keep a safe distance, while being able to intervene in a split second.".

In the event of a puncture, the mechanic literally jumps out of the moving vehicle, equipped with a wheel under his arm, while the driver parks the car, avoiding obstructing the movement of the peloton. A real choreography that we were unable to witness, to the delight of the leading riders, despite an 8-kilometer gravel section in the ascent of the incredible Col du Finestre at nearly 2,200 meters above sea level. At the end of May, snowfields are still present all around us!

Racing logistics... and car racing

Each vehicle is prepared the day before in a mobile base camp. Shimano has hubs in Spain, Benelux, Italy, Portugal, and Turkey. The current fleet includes 29 racing cars, around ten motorcycles, and vans, all maintained according to a strict protocol. "We have a mix of combustion-engine and hybrid vehicles," we are told. "The electric vehicles are not yet autonomous enough to last a 300 km stage with sporty driving," unlike those in the Tour de France publicity caravan, for example, which is now almost entirely electric; but with a much quieter ride.

Each year, a car can travel up to 15,000 km in racing conditions. The brakes, suspensions, and transmissions are put to the test. And visibility is paramount: all vehicles are repainted in Shimano blue with stickers that make them immediately identifiable to marshals and riders.

The onboard equipment represents a value of several tens of thousands of euros: carbon wheels, Di2 electronic transmissions, power meters, cranksets... and of course complete bikes (here from the Bianchi brand), equipped to withstand the worst conditions, such as those of the cobblestones of Paris-Roubaix or the Alpine stages.

Cutting-edge technology and impossible standardization

What is striking when observing the onboard equipment is the level of expertise required. The diversity of components makes standardization impossible: Shimano, SRAM, Campagnolo… disc brakes, 11 or 12 speeds, single or double chainrings, thru-axles or QR, pedals of all brands.

On the technology side, the neutral service must also juggle the latest innovations: wireless transmissions, on-board batteries, electronic seatposts, tire pressure sensors, high-pressure tubeless systems... All these components require in-depth knowledge of how modern bikes work.

"You can't just change a wheel and say 'it'll be fine.' The transmission has to work, the braking has to be optimal, and the rider has to maintain confidence," insists the mechanic. Hence the importance of the role: reassuring, intervening quickly, and sometimes... repairing while riding.

A team within a team

We often talk about riders as the heroes of the day. But in the car, we discover other faces, other heroes. Cycling enthusiasts, former riders or ex-professional team mechanics, who have chosen a different path. Shimano also makes a point of forming mixed teams, with an increasing proportion of women in the technical peloton.

The cohesion is palpable. Each member knows their role. There is a real hierarchy, a team spirit, a palpable solidarity in the event of a crisis. "We can save a rider's race, sometimes without anyone realizing it," the driver tells me. "And that's our greatest pride."

And then?

At the end of the stage, in Sestriere, while the riders are recovering in the team buses, the blue car stops in a technical area. The wheels are inspected, the bikes reconditioned, the batteries recharged, the water bottles emptied. One stage ends, another is in preparation. Tomorrow, the same operation on the last stage. For Shimano, the Giro is just one event among others: Tour de France, Vuelta, World Championships, Olympic Games... the ballet of blue cars continues, discreetly, professionally, with a regularity worthy of the best mechanical cogs.

Watching a Giro stage in the support car is like diving into another dimension of cycling: a world of extreme preparation, split-second decisions, and a simple but crucial mission—that the race can continue, no matter what. The neutral assistance service is at once a symbol of fairness, a logistical challenge, and a technological showcase for the world of cycling. An invisible hand, ready to act when the fate of a race can change over a simple broken spoke or a jammed chain.

0 Comments