Burn out, eco-anxiety, loss of meaning, rivalry with artificial intelligence… For the Belgian philosopher Pascal Chabot, who was one of the speakers at the “USI 2025” conference on Monday, June 2, dedicated to “the incalculable part of digital technology,” all these “contemporary pathologies,” referred to as “digitoses,” have the same starting point: the new connection of our consciousness to a “superconscious digital».

And to understand this, you have to remember how things were fifteen years ago, he begins. Imagine that you are drinking coffee with a friend and chatting.

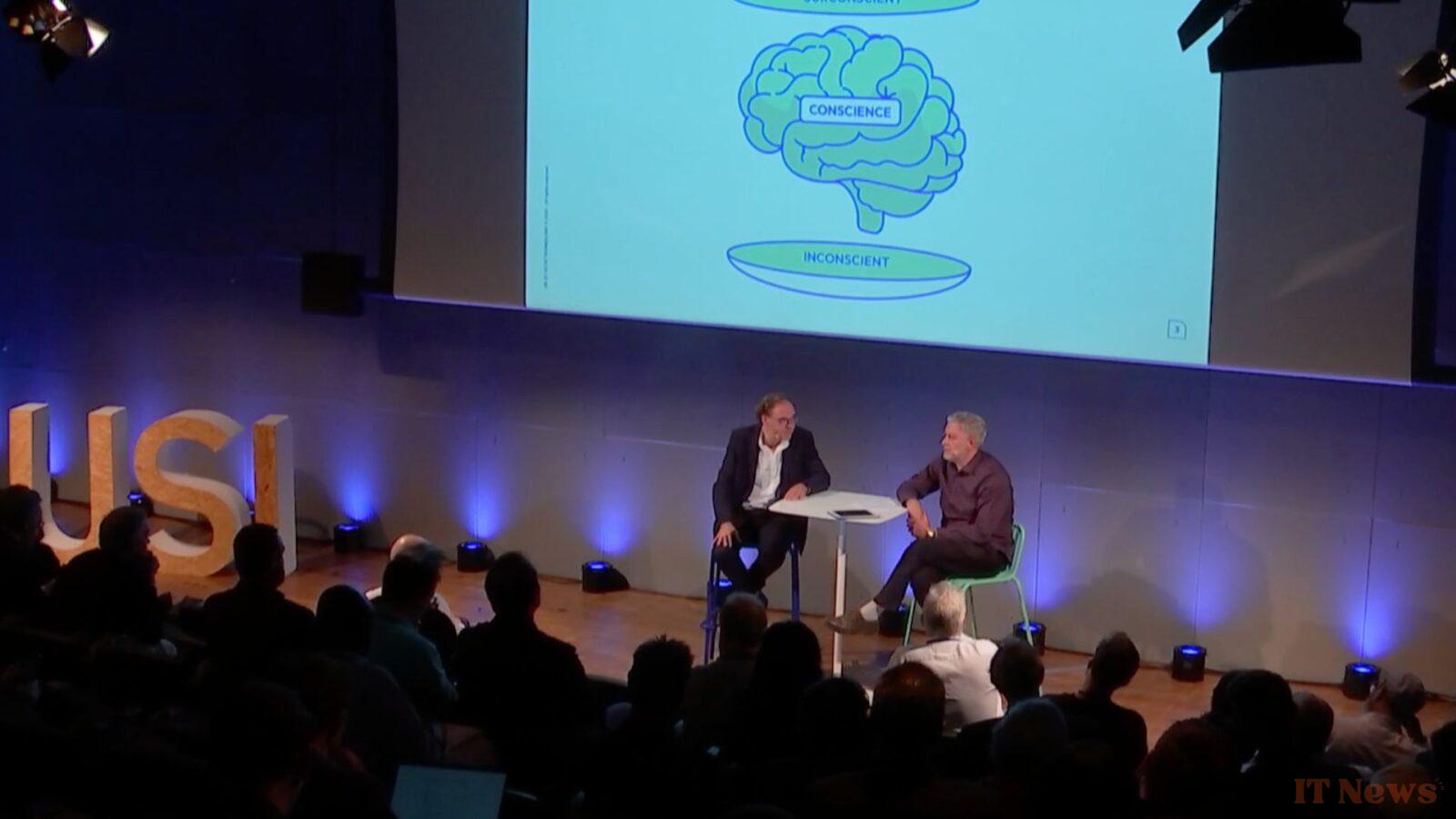

Once the interview is over, "you walk and during this walk, you dialogue with your unconscious. A series of things that were said will come back to you. You say, hey, that interested me. In this very spontaneous free association regime," we have "the coupling of consciousness and unconsciousness," he continues. But today, things no longer happen that way. "It's no longer your unconscious that you're going to call upon. You're going to do it right away," says the author of A Meaning of Life.

A New Connection to the Digital Superconscious

A gesture that we make more than 250 times a day: you're going to "consult your smartphone screen." However, this action, far from being trivial, "has produced a colossal change in our systems of meaning. That is to say, we're no longer connecting to our unconscious, but we're connecting to the digital 'superconscious'," a term described as "a dome of information, connection, network," "the machine-like and now digital environment that acts on us." In other words, "I don't talk to myself, but I'm interrupted in my thoughts because I go to check my phone."

And according to the philosopher, what we need to question today is "this new couple that we form with our (digital) superconscious, and also with the AI that we are using more and more. I say couple, because, for me, AI is not an entity external to human consciousness, but (it is increasingly, Editor's note) linked to our consciousness."And this constitutes a "radical metamorphosis," believes the Belgian thinker.

Especially since when consciousness and the superconscious are in contradiction, we face "digitoses," the "major contemporary psychological disorders" such as "burnout, eco-anxiety or rivalry with AI." Pascal Chabot then described these digitoses one by one, starting with eco-anxiety.

"A problem of trajectory and orientation"

"The world as it is, as we perceive it through our senses, feeds us a whole series of information. And between the world as it is felt and the world that is becoming, something is happening and that is a trajectory problem, a real problem of orientation. We call it eco-anxiety," he emphasizes. We say to ourselves, "this world is going to become either difficult to live in or transformed by climate change." And this results from "our knowledge of the future which is such that no previous generation has ever had it", he explains.

And if in the past, we didn't have to worry too much about the future, because it was "the repetition of the present", today, "if you are in front of a glacier for example, you take your phone (...) and you will have the four or five projections of the evolution of the size of this glacier (...). And there is a digitosis there. It can go very well for some people who bury their heads in the sand, or (who) have stories that will say, but no, we are still on a good trajectory", we will get through it.

But others will suffer from eco-anxiety, which we do not know, moreover, "very well what to do about". This is "one of today's mental pathologies for which, indeed, the classic psychoanalytic categories of neurosis and psychosis are absolutely ineffective," the Belgian thinker believes.

The split, the separation between being bodily there, while being very far away

There is also "split digitosis," described as a separation between being both bodily there and being very far away "at the level of the stories we tell ourselves or hear." Concretely, "in the professional world, we are at our workstation, the body is there, everything is fine. We respond more or less. But in fact, in terms of the stories we tell ourselves about our own work or the stories we hear, we are extremely far away."

It is a "digitosis that affects our relationship between sensations and meanings for a series of people," he continues. Another contemporary illness: burnout, about which the philosopher wrote more than fifteen years ago. "I saw it as a pathology of civilization," he recalls. "I said: we exhaust humans at the same time as we exhaust all resources, human resources as well as non-human resources. It's not for nothing. There is something there that is linked to a civilization of excess, to a civilization of injunction and also a civilization of continual connection to the superconscious," he continues.

With writing delegated to machines, we are entering a kind of post-history

Then comes the digitosis of rivalry, which "would already be felt unconsciously." "Rivalry is becoming ever more coupled with an artificial intelligence which, when everything works well, will allow us to increase our capacities. But rivalry (…) will very probably be experienced in a much more direct way," he suggests. For example, "we are in the process of delegating writing to machines." However, human history begins with writing, which is what separates history from prehistory, the philosopher reminds us.

"From the moment writing becomes less and less human, with machines writing well and almost better than us, (...) we enter a kind of post-history." And it "is impossible not to feel something like either frustration or dispossession, in any case, a rivalry with this world of artificial intelligence (...)," the intellectual believes. It is "a possible future, a future of humans increasingly coupled with a superconscious that will very likely take the lead over consciences," he suggests.

Pascal Chabot finally describes a final digitosis: the impossibility of doing quality work in certain companies, adept at "quickly done badly." This is "something that is extremely violent, when the injunctions concerning the work go against the person's quality standards." The latter will then work "in a sort of split: to deliver at that moment, (...) with such means," even if she would have "liked to do it completely differently."

And a company, "respectful of the people who work, trusts their own quality standards, because it is the people who work who best know the work to be done," explains the philosopher.

Human progress in crisis?

For the Belgian thinker, all these pathologies also stem from the split between "techno-scientific progress" and "human progress." "My hypothesis is that in reality, there are two main types of progress," he maintains. First there is the "useful, technoscientific, technoeconomic progress, like "all the phones you have used in your life", "the progress that drives our civilization and which accelerates because there is an invention capital which is such that (…) what has been invented has been invented once and for all and we benefit from it to continue this sort of forward march".

And besides that, "there is the progress human, subtle progress (…) progress in the art of being connected to others, in the art of being fair in what we say, in the art of being connected to the earth etc.». And this progress "is in crisis today. We have such dominant technoscientific progress that we would like to see it serve the development of human progress, of subtle progress. This is sometimes the case, but other times, (we see Editor's note) also a complete disjunction, a split". Now, true progress is not just technoscientific progress, it is progress that takes into account both the useful and the subtle.

0 Comments